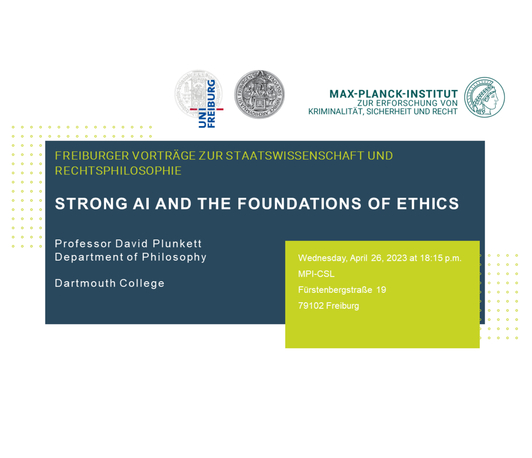

Strong AI and the Foundations of Ethics

Freiburger Vorträge zur Staatswissenschaft und Rechtsphilosophie

- Datum: 26.04.2023

- Uhrzeit: 18:00 c.t. - 20:15

- Vortragender: Professor David Plunkett (Dartmouth University, Department of Philosophy)

- David Plunkett is a Professor in the Philosophy Department at Dartmouth College. His core areas of current research include ethics (especially metaethics), philosophy of law, philosophy of language, philosophical methodology, epistemology, and social/political philosophy.

- Mitautor: Tristram McPherson

- Ort: Freiburg, Fürstenbergstr. 19

- Raum: Seminarraum (F 113) | Gäste sind herzlich eingeladen; Anmeldung erbeten

- Gastgeber: MPI-CSL in Kooperation mit dem Institut für Staatswissenschaft & Rechtsphilosophie der Universität Freiburg

- Kontakt: c.hillemanns@csl.mpg.de

A now-familiar thought (associated with the idea of “strong AI”) that in the not-too-distant future, AI may come to far surpass humans’ general cognitive capacities. Some famously worry that such AI pose an existential risk to humans, either due to indifference to human aims or a hostility to humans. This paper focuses on a different cluster of questions: a series of questions in the foundations of ethics raised by the possibility that we ask AI to engage in evaluative reasoning (e.g., about what is good and bad, right and wrong, etc.). There is a natural epistemic motive for asking strong AI to engage in evaluative reasoning: one might hope that strong AI could help us to make progress in addressing persistent evaluative controversies. However, suppose that strong AIs converge on evaluative conclusions that we are independently inclined to oppose. For example, AI might come to anti-anthropocentric evaluative conclusions (two examples: maybe they really prioritize certain cognitive capacities in their evaluations, treating us the way we treat mosquitos; or maybe they don’t, treating the interests of insects as on a par with that of highly rational beings). Alternatively, AI might come to radically consequentialist conclusions, that portray the evaluative significance of, e.g., our relations to our projects and loved ones as easily swamped. We take such dissatisfaction with (by hypothesis) epistemically highly credible evaluative conclusions to raise important questions about our attitudes towards the evaluative, even if we assume a strong sort of realism about evaluative thought and talk. It is familiar for metaethical antirealists to ask the question “why care about evaluative properties?” on the supposition that realism is true. And they often argue that this is a reason to reject realism. However, we think that the sorts of possibility we are canvassing instead makes salient two other ways of thinking about alienation from evaluative standards. First, it could push us to a conceptual ethics conclusion that we ought to adopt other (perhaps: more anthropocentric) evaluative concepts. Second, it might instead push us toward a deep alienation from the evaluative: that is, we might simply embrace that the our existing evaluative concepts capture what really and truly matters, and find that we simply don’t want our lives or world to be structured by what really and truly matters, if it involves sufficient sacrifice of what we care about. In light of these issues, we then reflect on how to best think about what “the” alignment problem in AI really is, suggesting that there are in fact multiple different “alignment” problems that are worth wrestling with, and that it is a difficult evaluative question which one to prioritize in thinking about AI ethics, and why.